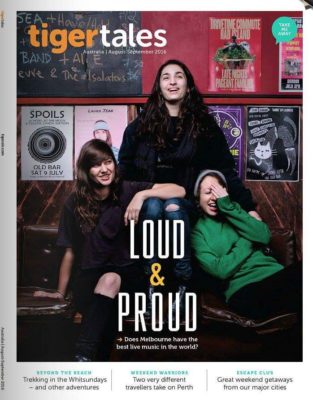

Cover story for Tiger Tales, inflight magazine Tiger Airways

It’s a Thursday evening at the Old Bar in Melbourne’s inner-northern suburb of Fitzroy, and Georgia Maq is ignoring doctors’ orders. The lead singer and guitarist of Camp Cope – one of the city’s most talked-about new bands – is supposed to be resting a seriously wounded throat. The word ‘haemorrhage’ is used. It sounds nasty. Talking is not recommended, and singing is most definitely out of the question.

Georgia is the only member of the trio to hail from Melbourne, but in this city that’s not unusual. Bass player Kelly-Dawn Hellmrich moved down from Sydney just over a year ago; drummer Sarah (Thommo) Thompson moved from the Gold Coast in 2009. Georgia had been playing as a solo artist, with her powerful voice, her rampant, unfiltered delivery and her ear for unusual, off-kilter phrasing soon catching the attention of many in the music scene, including Thommo’s boss at the record label she works at, Poison City Records. The two began jamming, and soon after met Kelly. The name came from a place where Kelly used to swim in Sydney, Camp Cove. “It was winter in Collingwood and I was homesick. These guys (Georgia and Thommo) were my way to cope with that, so we became Camp Cope,” says Kelly. Or as Georgia deftly summarises, “We’re a swimming hole!” Their debut self-titled album was released on Poison City Records in April. Despite the setback of Georgia’s voice, the band is relaxed and already planning their first overseas tour.

The optimism that now grips bands like Camp Cope and venues like the Old Bar can’t be taken for granted though. If it wasn’t for a remarkable show of community spirit a few years back we might not be sitting here today, raising a glass to yet another vital, burgeoning local rock band.

January 15, 2010 was possibly the darkest day in Melbourne’s proud live music history. The Tote Hotel, a venerable live music institution in the heart of Collingwood, announced that the venue would be closing its doors for good. While music venues in the city wildly regarded as Australia’s live music capital had regularly come and gone over the years, it was assumed The Tote would somehow always be there. Since 1980 the old building with the dark band room, the sticky carpet and the famous rock ‘n’ roll jukebox had hosted countless international touring bands, but more importantly had given a start to local bands who would contribute to the live music culture the city has become famous for. Two days after the unthinkable was announced police shut down the street. Two thousand people had gathered outside the front door to show support for their cherished pub. There was anger as well as sadness in the crowd. They knew it didn’t have to be this way. This gathering was the beginning of the biggest music community fight-back the city had ever seen, and the action in the months that followed would change the course of Melbourne live music history.

The Tote ran on tight margins, supported entirely by the music community. But changes to the liquor licencing regulations meant that any bar that had live music would now be placed under onerous security requirements. Bars like The Tote and the Old bar would now have to front up multiple security guards, which everyone, including the police, who had never had any trouble with live music venues, agreed was unnecessary. It was a cost The Tote simply couldn’t absorb. Rebekah Duke was working at The Tote at the time. “Anyone who ever went out to see live music in Melbourne knew that these places were about the safest bars you could go to. The new restrictions were just crazy. It was treating people like children.” The music community had a choice: to watch their scene die, or stand up and fight.

On February 23, 2010, only five weeks after The Tote announced it was closing, 20,000 marched in what became known as the SLAM Rally (Save Live Australian Music) down Bourke Street, ending on the steps of parliament. The crowd demanded that the government do more to support live music, and to recognise the vital part it played in Melbourne’s culture. Speakers included Paul Kelly, Molly Meldrum and Missy Higgins. It was a resounding success. The licencing amendments that automatically classified live music as ‘high risk’ were scrapped, and The Tote reopened, albeit with new owners. Rebekah remembers the day. “It was back, there to do what it does best, which is to have live music. It was like greeting an old friend.”

Rebekah is a testament to an often overlooked element for maintaining a strong live music scene: the work that happens behind the scenes. She’s recently launched her own creative consultancy company, Duchess Creative (duchesscreative.com.au). “I do everything from grant writing to booking, advice, crowd-funding and event production. I’m really interested in the mechanics of how something comes about. I’m fascinated by all the little cogs that fall into place to give the end result of a live music performance. There are a lot of people who come together to make it happen.” Rebekah says that the music sector has become a lot more politicised over recent years, as shown with The Tote’s death and resurrection. “We never really like to think that the law and music should intersect, but there has to be protection so musicians can keep doing what they do. We’ve seen out of the SLAM rally that voices have been heard and we can actually enact some positive change.”

Financial support is also vital if Melbourne musicians are to have their voices heard. Creative Victoria, a government body, has been busy awarding grants to musicians and bands that will allow them to record and tour. Marcus Hobbs plays in the band East Brunswick All Girls Choir. The name is a bit misleading: they are not all girls, nor are they a choir. They are however, the grateful recipients of a grant that helped them record their first album, Seven Drummers and have just been awarded a second grant for a new album, to be titled Dog FM. “The grants are important now only for us but for the flow-on effect it has through the whole community,” says Marcus. “It funnels through to local studios, engineers and venues. The amount of money generated from grants would vastly exceed the initial amounts offered.”

But it’s the opportunity to play regularly and meet like-minded people that has lured so many musicians to Melbourne. Jess Cornelius moved from New Zealand when she was 19, and fronts the band, Teeth and Tongue. “The community is a huge part of why Melbourne is so great for live music. It took me a while to really recognise and make use of that. There’s support, collaboration and of course competition.” She says the fun, low-key venues Melbourne has give a lot of colour to the scene. “You don’t have to dress up and you don’t need a shirt; but if you want to wear a neon body suit or pyjamas that would probably be okay, too.”

Back at the Old Bar, Kelly casts her fresh eyes on what sets the Melbourne music apart from the rest; what keeps it thriving. “A lot of the venues in Melbourne are owned by musicians themselves, and it just makes a world of difference. Here, the people working behind the bar and the people who run the bar are musicians. It helps build a tight community.”

Joel Morrison is one of those musicians. Along with Liam Matthews and Singa Unlayati he owns and books the bands at the Old Bar. “We’re coming up to ten years,” he says. “We were running another venue but the licence didn’t allow for bands at night. The Old Bar came up and it was just perfect for us. It’s what we love and what we do. We can have bands until 1am, every night of the week.” With no pokies and no food (although you’re welcome to order in), live music is the sole focus of the Old Bar. It survives on a loyal crowd of live music lovers and not much else. “It would be tough to run something like the Old Bar in any other city than Melbourne,” says Joel. “Melbourne has one of the best music scenes in the world – probably the best. There’s a massive culture that’s wrapped up in it.”

From the 1970s and 80s down in St Kilda, to Fitzroy in the 90s and now even further north into Thornbury and Preston the Melbourne live music scene follows where the musicians go. Rents may rise and gentrification may put the squeeze on, but a strong community will always find a way. Musicians living together, creating a scene, finding a space. Bands like Camp Cope have a lot to look forward to.

Next up for them is the Sad Grrrls Festival, to be held at Footscray’s Reverence Hotel on October 1. The name is a nod to the ‘Riot Grrrls’ feminist punk movement on the 1990s. As Georgia explains, ‘It’s a majority female lineup, so if you flip the genders it’s pretty much every other festival.’ It’s exactly the sort of thing you’d expect to see in a Melbourne, the city which nurtured Courtney Barnett, that is home to festivals like Meredith and Sugar Mountain, that in 3RRR and PBS has not one but two community radio stations of towering importance, that supports independent record shops like Thornbury Records, chocked with local vinyl, and that provides punters with quality live music every night of the week.

At the heart of it all is a bond over music, a common cause. “A lot of friendships are formed in the front bar of live music venues in Melbourne,” says Rebekah, “because you’re in there for the same reason. It’s like a rock ‘n’ roll church. You go there to commune with your fellow music lovers.”

Breakout box – Three best live music venues.

The Old Bar – 74 Johnston Street, Fitzroy. theoldbar.com.au

A dedicated live music venue with a small but well-equipped band room, beer garden and front bar. Bands play seven nights a week, with DJs after the bands finish. Home to the greatest football team in the world: The Old Bar Unicorns.

The Gasometer Hotel – 484 Smith Street, Collingwood. Thegasomterhotel.com.au

The only venue in town with a retractable roof that opens to reveal the stars, as well as a mezzanine viewing level. Front bar has nailed the warm pub vibe, with great meals and a bustling, welcoming atmosphere.

The Tote Hotel – 67-71 Johnston Street, Collingwood. thetotehotel.com

The home of rock itself, and a certified Melbourne institution. Large band room, with adjoining beer garden. The most famous front bar in town, where punters gather to talk, play pool and wait for the next band to come on stage. Like the words on its spray-painted front door: ‘Never say die.’